Iwalked New York Citys Soho History - SoHo is an acronym for South of Houston Street. The acronym which loosely describes the neighborhood’s locale within the busy New York landscape was also a brief nod to London’s similarly named district. SoHo was the first acronym applied to a New York City neighborhood and derived from a study titled the “South Houston Industrial Area” in an official document known as the “Rapkin Report” released in 1962. The report was issued by Chester Rapkin, a New York City Commissioner of Planning.

The area has seen numerous transformations from residential to commercial (and since returning to residential), but originally began as the first settlement for freed African Americans. Larger influxes of residents would not occur until the early 19th century after the stench and disease emanating from nearby Collect Pond was cleaned up and the pond filled in with land.

Diseases and stench would reappear, albeit in a different front, when SoHo made its name as the city’s red right district in the mid-nineteenth century. This reputational decline commingled with a more general migration of families further north in the city led to much of the area becoming abandoned by the late nineteenth century. Industry took advantage of building vacancies and the area took on a large textile presence. Once again the area faced a large exodus when the textile industry left after World War II.

This latest abandonment left the city seeking options for dealing with the countless empty warehouses in the area. One option that received a good deal of consideration in the 1960s was a proposed expressway that would link the East River bridges to the Holland Tunnel. This “urban renewal project” proposed by famed urban planner Robert Moses would require razing a good portion of the neighborhood. Residents vehemently fought the proposal and it was eventually squashed. Meanwhile, SoHo was slowly starting to fill its empty halls, or lofts, with a new series of tenants.

Led by the attraction of low rents and large loft spaces, SoHo slowly began to become an artist haven. Lofts were ideally suited for an artist’s needs to serve as both a living space and studio. The term loft actually developed in the nineteenth century to describe empty spaces on upper stories of building where sail making was performed. Usage of the term took on a more general use to eventually describe the upper stories of warehouses, factories, and other buildings which often resided on the ground floors. Today, lofts are common living space for many New Yorkers.

When artists first began to move into the area they did not always do so under proper legal terms. In some instances, artists would just “squat” in abandoned warehouses and in other instances landlords allowed them to live in substandard buildings in exchange for low rents. The city, concerned over tenants living in potentially hazardous buildings, attempted to make the residency illegal however this proved unsuccessful. In 1961, Mayor Wagner agreed to allow two artists to live in a single building, but only if the property was properly labeled as “Artists in Residence”. This signage also required the floor numbers on which the artists lived in the event that the structure in which they resided should catch on fire.

As more and more artists started to move to SoHo, new legislation to manage residency was required. The first such act came in 1971 when certain housing was set aside just for artists and was managed via the Artist Certification Committee. Approximately ten years later the 1982 Loft Law ensured that escalating rents would not become a deterrent. Rent stabilization was enacted on many lofts and this preserved the integrity and feel of the neighborhood for many years. Beginning within the last twenty years, as rent stabilization has slowly begun to be phased out in some areas, SoHo has started to become one of the pricier neighborhoods in which to live.

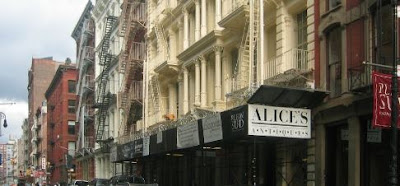

One attraction that has long brought with it the desire to live in the area is its beautiful cast iron architecture. Cast iron was first developed in the twelfth century for usage of tools but not integrated into architecture until the 1770s when it was unveiled in Paris, France and Liverpool, England. Its popularity grew after the display of the Crystal Palace with its ornate iron façade (1850-51, Joseph Paxton) during the London Great Exhibition of 1851. Suddenly more and more buildings began to be developed with cast iron in London and Paris. A large portion of the attraction transcended from both the ease of construction (buildings were being erected in four months or less) and the ability of developers to ornately mold the material into intricate designs. And if a piece broke off during its shaping? Well, just melt it down and start over. One perceived benefit that did not prove advantageous was the belief that cast-iron was fireproof. Unfortunately, later circumstances would show (in examples such as the Great Chicago Fire in 1871) that while the material would not catch fire, it did melt.

Two men who helped shape and develop the cast iron landscape of SoHo were James Bogardus and Daniel D. Badger. James Bogardus was an American architect whose styles were so unique with his cast iron craftsmanship that he actually patented his own style in 1850. His interest in cast iron began during a visit to Europe in 1836. Four years later upon settling in New York City he developed a five-story factory where he began manufacturing cast iron for construction. His first cast iron work within the city at 183 Broadway was built in 1848. Unfortunately that building has since been destroyed. He would also begin to design buildings across Baltimore, Chicago, Havana, Santa Domingo, San Francisco, and Washington D.C.

As building records around this period are scarce only three existing New York City buildings have been successful attributed to Bogardus (85 Leonard Street, 254 Canal Street, and 63 Nassau Street) but his influence is seen throughout SoHo. Bogardus, in addition to being a successful architect, was quite the prolific inventor as well. His was officially awarded thirteen US patents in his lifetime which included clocks, a grinding machine, gas meters, a postage stamp maker and a refillable lead pencil.

The other leading force in SoHo’s cast iron development was Daniel D. Badger who got his start in the iron industry via a foundry in Boston. He moved to New York City in 1846 and opened his own foundry located at 42 Duane Street. The company, the Architectural Iron Works, became renowned for its iron shutters and cast iron facades. Badger’s works are seen through both the SoHo and Tribeca area. Within the Tribeca East Historic District alone there are fourteen buildings which have been attributed to the Architectural Iron Works. iwalkedaudiotours.com

|

| New York Citys Soho History |

Diseases and stench would reappear, albeit in a different front, when SoHo made its name as the city’s red right district in the mid-nineteenth century. This reputational decline commingled with a more general migration of families further north in the city led to much of the area becoming abandoned by the late nineteenth century. Industry took advantage of building vacancies and the area took on a large textile presence. Once again the area faced a large exodus when the textile industry left after World War II.

This latest abandonment left the city seeking options for dealing with the countless empty warehouses in the area. One option that received a good deal of consideration in the 1960s was a proposed expressway that would link the East River bridges to the Holland Tunnel. This “urban renewal project” proposed by famed urban planner Robert Moses would require razing a good portion of the neighborhood. Residents vehemently fought the proposal and it was eventually squashed. Meanwhile, SoHo was slowly starting to fill its empty halls, or lofts, with a new series of tenants.

Led by the attraction of low rents and large loft spaces, SoHo slowly began to become an artist haven. Lofts were ideally suited for an artist’s needs to serve as both a living space and studio. The term loft actually developed in the nineteenth century to describe empty spaces on upper stories of building where sail making was performed. Usage of the term took on a more general use to eventually describe the upper stories of warehouses, factories, and other buildings which often resided on the ground floors. Today, lofts are common living space for many New Yorkers.

When artists first began to move into the area they did not always do so under proper legal terms. In some instances, artists would just “squat” in abandoned warehouses and in other instances landlords allowed them to live in substandard buildings in exchange for low rents. The city, concerned over tenants living in potentially hazardous buildings, attempted to make the residency illegal however this proved unsuccessful. In 1961, Mayor Wagner agreed to allow two artists to live in a single building, but only if the property was properly labeled as “Artists in Residence”. This signage also required the floor numbers on which the artists lived in the event that the structure in which they resided should catch on fire.

As more and more artists started to move to SoHo, new legislation to manage residency was required. The first such act came in 1971 when certain housing was set aside just for artists and was managed via the Artist Certification Committee. Approximately ten years later the 1982 Loft Law ensured that escalating rents would not become a deterrent. Rent stabilization was enacted on many lofts and this preserved the integrity and feel of the neighborhood for many years. Beginning within the last twenty years, as rent stabilization has slowly begun to be phased out in some areas, SoHo has started to become one of the pricier neighborhoods in which to live.

One attraction that has long brought with it the desire to live in the area is its beautiful cast iron architecture. Cast iron was first developed in the twelfth century for usage of tools but not integrated into architecture until the 1770s when it was unveiled in Paris, France and Liverpool, England. Its popularity grew after the display of the Crystal Palace with its ornate iron façade (1850-51, Joseph Paxton) during the London Great Exhibition of 1851. Suddenly more and more buildings began to be developed with cast iron in London and Paris. A large portion of the attraction transcended from both the ease of construction (buildings were being erected in four months or less) and the ability of developers to ornately mold the material into intricate designs. And if a piece broke off during its shaping? Well, just melt it down and start over. One perceived benefit that did not prove advantageous was the belief that cast-iron was fireproof. Unfortunately, later circumstances would show (in examples such as the Great Chicago Fire in 1871) that while the material would not catch fire, it did melt.

Two men who helped shape and develop the cast iron landscape of SoHo were James Bogardus and Daniel D. Badger. James Bogardus was an American architect whose styles were so unique with his cast iron craftsmanship that he actually patented his own style in 1850. His interest in cast iron began during a visit to Europe in 1836. Four years later upon settling in New York City he developed a five-story factory where he began manufacturing cast iron for construction. His first cast iron work within the city at 183 Broadway was built in 1848. Unfortunately that building has since been destroyed. He would also begin to design buildings across Baltimore, Chicago, Havana, Santa Domingo, San Francisco, and Washington D.C.

As building records around this period are scarce only three existing New York City buildings have been successful attributed to Bogardus (85 Leonard Street, 254 Canal Street, and 63 Nassau Street) but his influence is seen throughout SoHo. Bogardus, in addition to being a successful architect, was quite the prolific inventor as well. His was officially awarded thirteen US patents in his lifetime which included clocks, a grinding machine, gas meters, a postage stamp maker and a refillable lead pencil.

The other leading force in SoHo’s cast iron development was Daniel D. Badger who got his start in the iron industry via a foundry in Boston. He moved to New York City in 1846 and opened his own foundry located at 42 Duane Street. The company, the Architectural Iron Works, became renowned for its iron shutters and cast iron facades. Badger’s works are seen through both the SoHo and Tribeca area. Within the Tribeca East Historic District alone there are fourteen buildings which have been attributed to the Architectural Iron Works. iwalkedaudiotours.com